from our Naturalist, Rosetta

Last month our Director of Education, Rachel, wrote about interpreting tracks in the snow to learn what animals visit Flat Rock Brook. Prior to the snowfall, our Land Manager Brian found a different kind of sign under a tree in our forest: pellets that had been cast (regurgitated) by a large bird of prey. As a teacher, one of my favorite classroom activities has always been owl pellet dissection. So, after the snow had melted, I convinced Brian to take me to the tree so that I could collect the pellets.

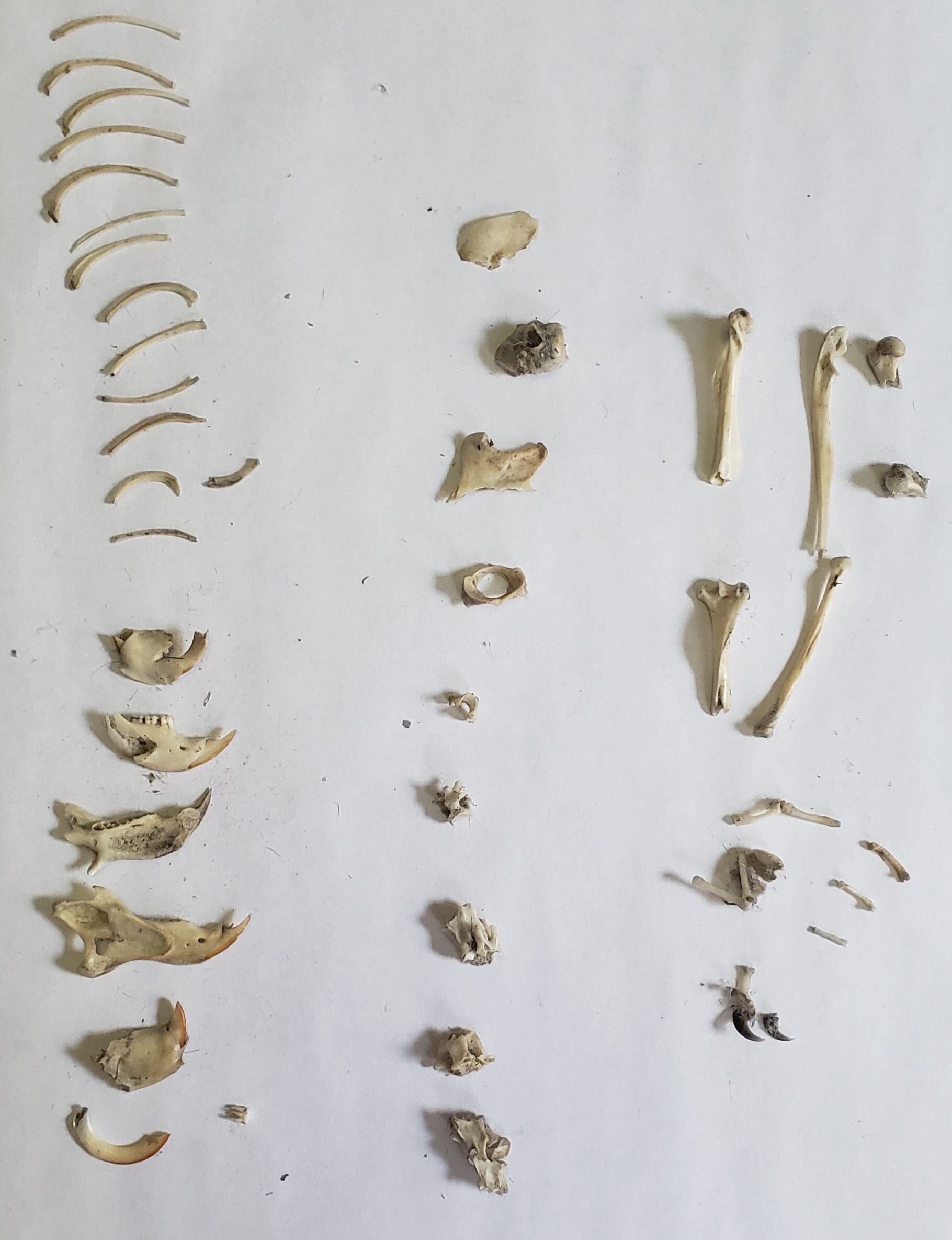

Pellets are compacted masses of fur, bones, feathers, teeth, and other undigestible material in a bird‘s meal. Many scientific supply companies sell owl pellets for use in the science classroom. Pellets can be carefully teased apart and the bones examined to learn to give us insight into the diet of the owl that cast it. In the classroom, the lesson frequently involves applying the findings to produce a food web with the owl as the top predator.

Because they are readily available for and used in the classroom, you are probably most familiar with owl pellets, but they are not the only bird that cast pellets. Hawks, eagles, falcons, and several other types of birds produce pellets as well. If you have visited our aviary, you may have noticed pellets in the birds’ enclosures. Our large birds cast pellets that are generally 2-3 inches long, and so they are easily visible on the floors of the great horned owl and red-tailed hawks enclosures. The small birds produce pellets less than an inch long.

The casting of pellets allows a bird to make room for its next meal. They typically cast a pellet every day. Owls gulp their food and swallow smaller prey whole, ingesting all of the bones along with the flesh. These bones are only slightly digested and persist in the pellets. Hawks tear at their food and have stronger digestive juices than owls. Thus, the pellets of hawks tend to be smaller than those of large owls and they contain fewer bones.

So, what kind of bird produced the pellets found under the tree at Flat Rock? We have several clues to tell us. Although the snow had caused to pellets to break down, the fur was still stuck to the bones when I retrieved them. Brian had seen the pellets when they were intact, and reported that they were larger pellets which means they were from a large raptor. Several of the bones were larger than the entire pellet of a small bird.

I eliminated the possibility that these were owl pellets. Since owls generally swallow their prey whole, one can often find nearly complete skeletons in their pellets, and the bones are frequently found attached to one another, especially the vertebrae. Hawks tear much of the flesh from their victims, and do not always swallow all of the bones, so I would not expect to find anything near a complete skeleton. Indeed, I found mandibles, ribs, and a few vertebrae, legbones, and toes, and only small pieces of skull.

With the help of taxonomic keys and illustrated sorting charts, it is possible to identify what the bird of prey ate, if not to the species level, but to general group to which it belongs. The largest mandible was that of a chipmunk. Although owls do prey upon chipmunks, it is more likely that a diurnal predator would prey on a chipmunk who has ventured outside of its den.

I had one more clue that the pellets were cast by a hawk and not an owl: the location of mutes (poop) around the tree. Raptors such as hawks and eagles “slice”, or squirt their poop way out behind them. Falcons and owls poop essentially straight down and don't slice. (You have probably noticed that our resident red-tailed hawks slice their mutes, as the mesh barrier is covered in “whitewash”. If one of them raises its tail with its back to you, move out of the way!) The mutes we found were not directly under the tree, but among the fallen leaves several feet from the tree where the pellets were cast as well as other trees in the immediate area.

So, given the size and contents of the pellets and the locations of the mutes, I infer that it was a hawk who cast its pellets under the tree. If I had to guess at the species, I’d say it was a red-tailed hawk because we have seen many of them flying through our forest, over the meadows, and visiting the aviary since last spring.

If you’re interested in dissecting an owl pellet on your own, they are inexpensive and easy to obtain. Owl pellet dissection should only be undertaken with sterilized pellets due to the risk of contracting bacteria or viruses. Sterile owl pellet kits are available through several online scientific catalogs. They are usually packaged for a classroom, but Home Science Tools is a good site to purchase just one or a few pellets.

If handling owl pellets is not appealing to you, check out this virtual owl pellet dissection that you can do online. It’s not as much fun, but it is much cleaner than dissecting a real pellet!